The following is a WWII story courtesy the Stamford

Advocate

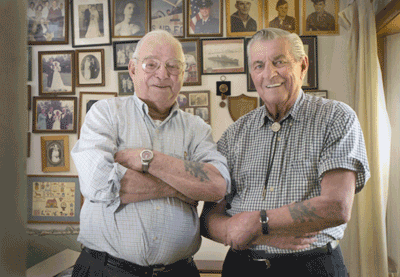

Lifelong friends Teddy Guzda, left, and Willie Kesnick, right, served on a U.S. Navy sub chaser during D-Day. They enlisted

together and had the U.S. Navy insignia tatooed on their left forearms.

Andrew Sullivan/Staff photo

Copyright © 2005,

Southern Connecticut Newspapers, Inc. |

June 6, 2005

‘They have the same angel’

Buddies reflect on surviving D-Day

By Angela Carella

Advocate Staff Writer

STAMFORD – It was a heck of a day to lose a helmet.

Bullets were flying, bombs were exploding, shrapnel and hot machine-gun shells were raining on him, and Willie Kesnick was bare-headed.

It was June 6, 1944, the day the Allies invaded Normandy, and Kesnick was an 18-year-old coxswain firing a gun aboard Patrol Craft 552, the U.S. Navy's control ship for the attack on Omaha Beach. But he didn't have to worry.

Ted Guzda, his childhood buddy, was at his back firing another gun. Guzda, who was the same age and rank, spotted a bucket of sand on deck nearby, emptied it and tossed it to Kesnick.

"Here, put this on!" Guzda shouted.

Kesnick remembers the noise.

"Ping! Ping! Ping! It was our own shells hitting the bucket on my head as we were shooting," he said.

From the fortified coast of France, the entrenched Germans were firing at the ships in the English Channel. German fighter planes strafed them. The bombardment, along with mines and steel barriers planted in the surf, sank the Navy's first wave of amphibious tanks, filling the water with bodies.

Kesnick thought it would be the last day of his life.

"Hey, Ted," he called. "How do you pray?"

"I said, 'Pray? Willie, just keep that bucket on your head,'" Guzda remembered.

Aboard the rugged little warship on this day 61 years ago, he and Kesnick were among 135,000 American, British and Canadian troops and 20,000 vehicles that attacked five beaches in Normandy. France was where the Allies thought they had their best chance to penetrate the Atlantic Wall, a nearly impregnable defense the Germans built along 2,400 miles of European coast.

Dubbed D-Day, it was the beginning of the end of World War II.

For a couple of guys from Stamford who wanted to be on the water, see the world and "get those sons of bitches who bombed Pearl Harbor," it was more than they could have bargained for, but "being together made it so much easier," Guzda said.

"When we went into a fight, we were together," Kesnick said. "That was something special."

The veterans, now 81, have twin tattoos. On his left forearm, each has an eagle with stars on either side of its head, "U.S. Navy" printed under its claws.

"We got them at a Brooklyn barber shop, near the Navy yard," Kesnick said. "Twenty-five cents each."

"Every time we went ashore, we were together," Kesnick said.

"We sat down and wrote letters home, side by side," Guzda said.

"Our lockers were open to each other," Kesnick said.

"Whatever was his, was mine," Guzda said. "Whatever was mine, was his."

It's a friendship footed in their Polish heritage, forged by neighborhood ties, and fortified in war - as enduring as the tattoos inked in their forearms.

They met when they were boys growing up in Waterside, a neighborhood along Stamford Harbor, where Guzda was born. Kesnick moved there from Bridgeport when he was 1. Kesnick's father had a grocery store; Guzda's parents were his customers.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Guzda walked along the train tracks from Stamford to New Rochelle, N.Y., with his brother, Mathew, one year older, who was joining the Marines. Guzda wanted to join the Navy.

When they got there, they found only a Marines recruiting office. So, the next day, Ted Guzda walked the train tracks in the other direction, to New Haven, where the Navy signed him up.

About that time, Kesnick joined the Navy, too. Several months later, he was aboard PC 552, docked at the Navy base in Staten Island, N.Y. Guzda was repairing ships there. They met, and Kesnick got an idea.

"I told Ted, ‘I'll get you aboard the 552,' " he recalled. "I went to my captain and said, ‘I've got a good man out there. You'd be happy to have him aboard.' "

The captain decided he could use him, and Guzda joined the crew of the 552. But something went wrong with the paperwork. Shortly after, when the ship was on its way to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the captain got a telegram. It ordered him to put Guzda under arrest for desertion.

"I had to go back to Staten Island and face the admiral," Guzda said. "He asked me, ‘What are you doing aboard that ship? Do you have orders?' I told him what happened and he said, ‘For your punishment, get back aboard that ship and stay on it.' "

Soon the PC 552 was on its way to Europe. Kesnick began to keep a diary:

Thursday, Jan. 20, 1944 - Ship was supposed to get under way. It was so rough that we couldn't leave port. Found out for sure where we are headed - England.

Friday, Feb. 11, 1944 - Went out to sea with a bunch of invasion ships.

Sunday, March 12, 1944 - Patrolling while the invasion ships unload.

April 27, 1944 - Five Landing Ship Tanks hit and about 400 sailors and soldiers died. This happened right behind our convoy.

May 27, 1944 - We had bad luck. We rammed into a ship loaded with rockets, which put a big hole in our bow.

Saturday, June 3, 1944 - Fixed our ship. All set for the big day.

Just before the invasion, the English Channel was crowded.

"There were so many ships out there that you didn't know if they were enemy or not," Kesnick said. "You had to wait for a signal."

The attack on Omaha Beach began with a wave of amphibious tanks loaded with troops. Launched from ships in the channel, nearly all sank.

"We started picking up survivors. We took on 14," Kesnick said, showing a copy of the ship's log dated June 6, 1944. "Saving lives was good. It's better than killing somebody."

They picked up a lot of bodies, Guzda remembered.

"Later we had to sink most of them," he said. "We took off whatever identification they had, put weights on them and sank them. There was nothing else we could do."

The Germans were a formidable enemy, the veteran sailors said.

"They invented buzz bombs to attack England. They had the best aircraft. They put mines everywhere. When our ships were in the harbor, they sent divers down to attach explosives to our propellers," Kesnick said. "They had these huge flares that they would shoot up at night and they would hang in the air as if they were on parachutes, lighting up our whole convoy so the Germans could photograph what we had, or shoot at us. We called them chandeliers."

"They had these one-man, single-torpedo submarines that would come after us," Guzda said. "I still don't know how we won the war."

Death was close on D-Day.

"When we left, they told us, ‘God bless you, 552.' They didn't expect us to come back," Kesnick said.

"All it took was one bullet. To this day, I don't know how we got missed," Guzda said.

His daughter, Laurie McAvoy, has a theory.

"They have the same angel," she said.

Maybe so. Someone watched over them even after the war.

Kesnick left the Navy in 1947 and opened a liquor store on Greenwich Avenue in Waterside. He married and had two children. He ran the liquor store for more than four decades and was held up at gunpoint four times - pistol-whipped one time and shot in the shoulder in 1996, when he was 73.

"I survived that, I survived the war. God loves me," Kesnick said.

His wife, Vera, died four years ago. They have four grandchildren.

Guzda stayed in the Navy until 1951. He wanted to make a career of it but his family drew him home.

"I came back on leave for the birth of my son, Paul, but I missed it. By the time I saw him, he was 6 months old. He cried when he saw me," Guzda said. "Then I knew I had to leave the service."

He joined the Stamford Police Department and walked a beat for 32 years, a job he loved. He and his wife, Helen, had four children, including Paul, now a Stamford police sergeant. Helen died three years ago. They have six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Guzda never saw his brother, Mathew, again. The Marine was killed at Guadalcanal in the Pacific. Guzda got a telegram while his ship was in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. He has searched for Mathew's body.

"I don't know where he is buried," Guzda said. "They told me Hawaii, but I went there and I couldn't find his grave. Then I heard it was Samoa, but there is no American military cemetery there. I don't know if he even was buried."

For 60 years, he and Kesnick rarely discussed World War II.

"I didn't think anybody would believe me," Guzda said.

They decided that, if they were going to talk about it, they'd rather do it together.

"It's good to tell a story while a friend is with you to prove what you are saying is the truth," Kesnick said.

Life has blessed them with many things, they said, and one of the best was having a buddy at their backs.

"It was a pleasure to have someone you knew right beside you," Kesnick said.

Copyright © 2005, Southern Connecticut Newspapers, Inc.

All Rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Related Oral History and Photos, WWII Exhibit