| Join | Official Historian | City of Stamford | Blog | About Us | |

| Jewish Historical Society | Civil War Roundtable | Contact Us | |

|

|

|

|

Crandall – The Farmer-PoetBy Edward F. Bigelow, ArcAdiA: Sound Beach, Connecticut.Guide to Nature Magazine, Vol. VII. July 1914. No. 2.

VERY farmer should be a poet. Every farmer to a certain extent is a poet, although he may not realize the fact. With many that extent is limited. It is a question of degree, but any one that loves nature sufficiently well to abandon the crowded haunts of man for the seclusion of a farm in the distant country, there to deal directly with Mother Nature, has in his heart the germ at least of the true poetic instinct. This, to a limited degree, is true of any occupation in life. There is poetry in every form of activity, as there is in every spoken word, although one must sometimes search long and faithfully to find it. One may be a poet without writing poetry. Few have the power of poetical expression, but every man that likes to live with the trees and the birds and that likes to plow, likes to see the sun rise, and likes to drive the cows to pasture, is a poet. So is he that takes shellfish out of the sea, or pounds iron on the anvil, or sells ribbon or pills or harrows. It is doubtful if there can be found in all the world a human being so sordid, so utterly utilitarian as not sometimes to have uplifting thoughts, some appreciation of the beauty of living and of acting and struggling faithfully in life's contests. This is a world of specialization. Comparatively few supply the things that everybody uses. This is as true of poetry as of everything else. We all may speak poetry and live poetry, but it remains for the specialist in versification arid in rhythm to put into transmittible shape the thoughts that are common to humanity. If there were no users of plows and pills and ribbons, plows, pills and ribbons would not be supplied. If there were no lovers of nature this magazine would not be needed, If there were no people that desire to know about other people's doings and the events in human progress, newspapers would not be needed. Editors and publishers are comparatively few although everybody likes to read the newspapers. Although everybody directly or indirectly depends upon the blacksmith, comparatively few stand by the glowing forge. Such thoughts were in my mind as I made an appointment to go northward from Stamford to visit Idylland. It was a journey to the home of one that not only lives amid beautiful surroundings, that knows the delight of chopping wood, of holding the plow, and of seeing green things grow, but one that can in well written lines transmit some of that joy to others.

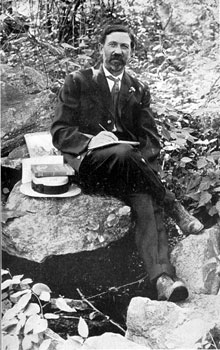

Mr. Charles H. Crandall is a poet pre-eminently of the farm, though he has written upon other topics. To him the field, the forest, the sky and the streams, mean more than the place in which he raises his crops, gathers nuts or hews firewood, although he is engaged in all these interesting occupations as well as in other diversified pursuits characteristic of the New England farm.

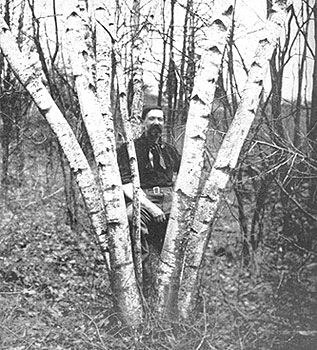

He lives near to nature. I wish that I could write in glowing terms of his interest in nature study, but I cannot. I wish that he were a naturalist, but strictly speaking he is not. He is a farmer and farmer-poet; he appreciates the delights of his occupation, he transmits his pleasure in it to humanity, and he interests humanity in it, but for the details of nature, as the naturalist sees them, he has no special affection. I doubt if, when he looks at a pine tree or an oak tree or an apple tree, he can describe any of the details of xylem, phloem, of cambium layer, or of stomata, but he does see in the pine tree, the oak tree and the apple tree, something perhaps more important. He sees human life exemplified and he sees various kinds of people with their characteristics and diversified occupations symbolized by the trees. It is for the farmer to be strong like the oak. It is for the pine to seem graceful and cultured and refined, but it is for the apple tree to scatter fruit for all the people. When Mr. Crandall looks at those trees he writes not of their scientific structure, nor of their physiological functions, but of what they mean to humanity. Witness his poem, “Three Trees.” Three Trees

When Mr. Crandall early in the morning goes forth to his field, he never stops to pick a bit of moss from the wayside to examine it with the microscope. He looks toward the rising sun and hears the robin's call, and to him they say, “Go to work.” He sees the plow motionless in the furrow, the glowing colors of the morning sky, he hears the music of the falling meadow bars, and they all speak to him of happiness. He thinks of the day's work.

The swift flight of the birds tells him that he too must be busy until the twilight falls, when again the meadow bars shall fall as the cows come home from the pasture. What glorious music it is to him! How different from the flight of the birds, for hearing some one say, “Come, Love, there is no more work to do.” Such are the thoughts that arise in his soul, and urge him onward toward the day's duties, and enable him to appreciate the rest that will follow. It is his peculiar talent to transmit that feeling for the day's work and the night's rest, to thousands that toil in the fields. Where is the farmer that will not appreciate his poem that he calls “The Happy Farmer?” The Happy Farmer.

Speaking of the farmer's rest will remind those that have toiled with the plow or with the scythe, of the strenuous life that the farmer leads. It is everyday toil, delightful toil, it is true, but despite the fancies of the poet, and the alluring misrepresentations of the people so enthusiastic over the enchantments of the soil, it still remains toil, nothing but toil if one can see in it only the toil. But to the farmer the toil itself is a joy. He would not desert his occupation for the frivolities and artificialities of the city, but he does appreciate the rest that comes at the end of his honest labor. How different is an active city man's rest from that of the farmer! Ten hours, twelve hours in his city office; the work drives him. When his time for rest arrives, he dashes away in his automobile, and with his family goes whirring through the country with the same rush, the same dash, the same spirit that have inspired him all day long in that city office. But that is no rest for the farmer. He thinks of the fisherman as enjoying the ideal rest, as he plods in the furrow behind the plow, or swings the scythe in the scorching field, he thinks, “Could I but sit in the tear of a boat on a placid sea and fish, and fish; and fish, even if I never caught a fish !” As he swings the axe and thinks of the fisherman that pulls the oars, he says, “Could I but stop for a time this swinging as he can stop that pulling!” And there you will discover the germ of one of the finest poems that Mr. Crandall ever wrote, “Lean on Your Oars and Rest Awhile.” Lean on Your Oars and Rest Awhile.

When the day is done, the farmer takes his pipe and under the shade of the trees he thinks and thinks of the former days under the trees, when as a boy, he played amid the murmur of the leaves, the music of May, and heard half unconsciously the robins' song amid the gentle murmur of the homing bees. The remembrance of these comes now like the loving caresses of a mother gone long ago. Then his mind wanders to those days when, as a farmer boy, he looked toward the time when he might go fishing, when the toil of stirring hay should give place to the drifting of a boat. That skiff floats on the sweetest part of life's stream. There he leans on his oars, and rests awhile.

A lady recently came to ArcAdiA and said that she wanted to study the birds. She had come from a distant state, because she had heard that the ornithology of this part of Connecticut shore birds and land birds in great numbers. She wanted to add to her list. She had “checked up” one hundred and thirty-five in the previous year. “Done what?” I said. “Checked up,” she repeated, “don't you know what that means?” Yes, alas! I do. It means that the birds meant little to you if checking up is the whole thing. Being required to learn the names and so as to identify a dozen trees, does not mean much, alas! not much. But to have a tree give you new life when you are tired of the foolishness of the metropolis, tired of the pavement, then the tree will mean something to you. Not a matter of identification, not a matter even of learning scientific details. One partridge that sits watching you unafraid means more than a hundred and thirty-five that you have checked up. When I walked through the ravine with Mr. Crandall, a commonplace chewink called and Mr. Crandall asked me, “What is the name of that bird?” He saw the spring flowers in bloom and the common saxifrage, and wanted to know the names. Our farmer-poet has gone deeper than names and “checking up.” The things of the forest have meant more to him. Over the green leaf on the tree top he has soared to distant stars and nebulae. To learn more than their names “he questioned the universe,” and the answer brought him, not mere knowledge and pastime, but help and trust and joy. We commend to our readers his delightful poem, “The Forest Cure.” The Forest Cure.

But here near his home where everybody knows him and loves his verses, how vain it is for me even to attempt to analyze Charles H. Crandall's poetry. It is poetry, not to be dissected but to be left as nature is to him around his home. He has seen and described the beauty of the commonplace. Our readers will recollect that several months ago a potato in the form of a heart came to this office. It was sent by a kind friend who had welcomed it as an emblem of a heart hidden in the bosom of Mother Earth. In that conventionalized form it represented the fruition of a new life, a resurrection of a life that had vanished. Most of us would have seen only an oddly formed potato. Farmer Crandall looked beyond the mere vegetable to the thought and uplift and encouragement that that odd form inspired. Here is what he saw: “Heart's Love Remains.”

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|