| Join | Official Historian | City of Stamford | Blog | About Us | |

| Jewish Historical Society | Civil War Roundtable | Contact Us | |

|

|

|

|

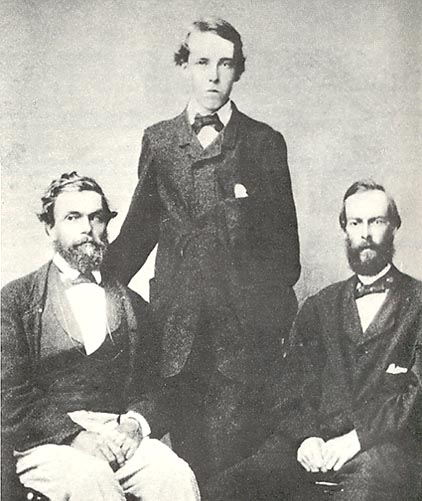

The Saga of the Clipper Ship Hornet and the Ferguson Brothers of Stamfordfrom Newsletter, Volume 49, Issue 2, The Stamford Historical SocietyIn the nineteenth century, there were but a few therapeutic options available to those afflicted with tuberculosis. Twenty-eight year old Samuel Ferguson of Stamford suffered from this illness, so in January 1866, he and his younger brother Henry (a sophomore at Trinity College, Hartford), booked passage on the clipper ship Hornet. Their destination was southern California, where it was hoped that the regions' dry, warm climate would restore Samuel's health. Scheduled to sail from New York, around Cape Horn, the ship was commanded by Captain Josiah A. Mitchell of Maine, an experienced, capable mariner in charge of this vessel's fifth passage to San Francisco prior to the Civil War. Since Samuel and Henry were the only passengers aboard, they would dine with the Captain, who enjoyed discussing a broad range of topics with them. Once they unpacked their belongings, which included a number of books, for both brothers were avid readers, they settled into what seemed to be the beginning of an interesting and enjoyable experience. Henry spent part of his days studying Greek, Math and Latin and observing how the crew handled this fast clipper ship. Samuel read contemporary literature and enjoyed a glass of claret with the Captain during dinner. The brothers entered in their diaries sightings of whales, dolphins, flying fish and other marine creatures as well as detailed meteorological observations.

However, disaster occurred on May 3, when sailing in the Pacific Ocean, west of South America. A member of the crew began drawing some varnish from a barrel below deck, using an open flame lamp for illumination. The vapors immediately ignited and quickly spread throughout the wooden vessel. Samuel and Henry together with the Captain and crew gathered as much food and water plus charts, compass, sextants, chronometer, together with scant other items and scrambled into three boats. Once safely away from the burning vessel, they ceased rowing hoping another ship might see the flames and come to their rescue. Unfortunately this did not occur. With only ten days worth of provisions, the survivors spent the next forty-three days on the high sea in an open boat, covering over 4,000 miles. Both brothers and the Captain saved their diaries, which they continued to keep throughout the ordeal. At first the men were in a longboat and two quarter boats, tied in tandem, each with a small sail. Towards the end of May the Captain decided that the three boats could not continue sailing in this manner. The First Mate offered to cast off his line. So the Captain divided the scant food and water supplies equally, gave them a compass together with other navigational aids and wished them good luck. They came upon each other one more time, parted with the Second Mate's boat, and were never seen again. Now fifteen men began existing on scant reduced rations for the next three terrifying weeks. At regular intervals, Captain Mitchell and Henry would read prayers aloud, noting that most of the men seemed attentive and drew comfort from them. By utilizing the sail and buckets for catching rain, the men were able to gather water, but as their ordeal wore on, they encountered fewer storms. At first they did catch some fish, turtles and birds to augment their meager supplies. However, after several weeks this food source suddenly diminished and then ceased. Hunger and thirst took their toll; some began suffering from delirium, imagining and plotting—on the very edge of madness. On June 5th there were mutterings amongst three or four men against the Captain and passengers. They blamed them for their situation proposing murder and cannibalism. Fortunately, word of this reached Captain Mitchell. He kept a hatchet hidden by his side and hardly slept. The Ferguson brothers remained on alert, sleeping in shifts. Written on the last page of Henry's diary is a note written to Samuel regarding certain men who could be trusted and to watch his pistol and cartridges. Luckily, the need for these weapons never arose. June 9th they finished their last provisions, a tin of soup divided between all of them, with a minute amount of water. Now in extreme desperation they began eating their boots. Finally, after six more days of tormenting hunger and thirst, they sighted the island of Hawaii. Too weak to navigate their craft between the reefs, they would have perished were it not for two islanders who swam out and helped them make landfall. They had arrived at a missionary settlement, the only inhabited location for miles around. Unable to walk or stand, they were carried up the beach into this small community and received the care so desperately needed. Thanks in part to Divine Providence and Captain Mitchell's exceptional seamanship, the survivors were at last safe. At the same time, on island of Oahu, there was a young newspaper reporter named Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain) who heard an account of a boatload of shipwrecked, starving men. Although physically indisposed with saddle boils from excessive horseback riding, he sensed a story. With the assistance of Anson Burlingame, U. S. Minister to China, Clemens (Twain) arranged to be transported on a stretcher to the island of Hawaii. Accompanied by Burlingame, he interviewed the Hornet's remaining crew and was immediately returned to Honolulu. He stayed up all night preparing his copy and was able to deliver it the following day to a ship that was leaving for San Francisco. The story was a sensation with newspapers throughout America reprinting it. On their return voyage to California, Clemens (Twain) further interviewed the Ferguson brothers and Captain Mitchell. They let him examine their diaries, excerpts of which he incorporated into an article titled “Forty-three Days in an Open Boat. Compiled from Personal Diaries.” Submitted to Harper's New Monthly Magazine, they published it in December 1866. Thirty-three years later he reworked portions of it, gave the story a new title, My Debut as a Literary Person and handed it in to The Century Magazine, where the article appeared in November 1889. The story was included in The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg and Other Stories and Essays, Harper and Brothers, 1900. In this work, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) stated it was not the Jumping Frog story that launched his literary career, but the saga of the survivors of the clipper ship Hornet. After a brief Hawaiian recuperation, the Ferguson brothers returned to California. Samuel never recovered from his illness, made worse by his ordeal at sea. He died in October of 1866 and his remains were shipped back to Stamford for burial. Henry returned to his studies at Trinity College, graduated and went on to become a respected member of the clergy and a professor of history and politics at his alma mater. Ultimately, Henry returned to serve as Headmaster of St. Paul's School, in New Hampshire, from which he had matriculated so many years before. Mark Twain's correspondence

with the Sacramento Daily Union - 1866, Twenty-five letters from the Sandwich

Islands (Hawaii) Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) (1835-1910) |

|||

|

|