Education Spelled Freedom

Education Spelled Freedom

From:

Stamford Past & Present, 1641 – 1976

The Commemorative Publication of the Stamford Bicentennial Committee

The little one-room schoolhouse played a major role in preparing the American colonists to resist and finally overthrow British tyranny. In contrast to the common people of Europe – illiterate throughout the eighteenth century – many of the colonists in Connecticut and Massachusetts could read and write. The early settlers had brought across the Atlantic the most advanced educational ideas of the time. Without an educated populace, it is unlikely there would have been an American revolution.

The Puritans who emigrated from Massachusetts Bay to Connecticut stipulated in their first law code of 1650 that everyone be taught to read English and be instructed in a trade. They believed that a person should be able to read the Scriptures and understand the doctrines of faith in order to foil “the old Deluder,” Satan.

In Stamford, the first public schoolhouse was a crude, unheated wooden structure only ten or twelve feet square. It was built in 1671 as part of the town's first “urban renewal” project. That year, the settlers tore down their original meeting house, outgrown at the end of thirty years, and used some of the timbers to put up a school near the present Old Town Hall on Atlantic Square. Nearby, on the common, they built a new meeting house thirty-eight feet square. The meeting house also served as the Congregational church, where the minister preached the precepts of the small settlement's only accepted religion.

Prior to the schoolhouse, Stamford children learned their lessons from their mothers or in a Dame School where a housewife would collect neighboring children and attempt instruction. Usually the children helped with simple household tasks such as washing dishes or shelling peas, and the little girls learned to “knitt and sowe.” As a rule, Dame Schools were not very satisfactory.

After it was decided to build a school, the town meeting of November 31, 1670, voted to “putt down all petty scools yt are or may be kept in ye town which may be prejudicial to ye general scoole.”

It had been voted at a previous meeting that “Mr. Rider shall be admitted to the town for a time of trial to keep schoole.” Mr. Rider's teaching “trial” was unusually short. Records for December 24, less than a month later, state that “the town is not minded to hire Mr. Rider for a school master anymore. Mr. Bellamy is hired instead.”

At a time when the simple ability to read and write was the mark of an educated man, almost any literate male from age fifteen up could become a schoolmaster. Usually the Congregational minister had considerable influence in selecting a teacher, and any young man who voiced unorthodox opinions would quickly be turned down. Teachers in “common schools” were not trained; they learned on the job. But there were fringe benefits. Schoolmasters were exempt from military, poll and estate taxes and from road repair duty. The more frugal communities sometimes hired women teachers, because women were paid lower salaries.

Even in earliest colonial days, good education was of “public concernment” in Connecticut. It was mandatory as of 1657 that every settlement of fifty or more householders in the New Haven Colony, of which Stamford was a part, must have a school and a schoolmaster. Each child paid a “fare” to the schoolmaster, and the town in general paid “one-third part.”

The crux of education in Stamford and elsewhere in the colony was obedience to a set of standards. Stamford's early farming society cultivated not only the rocky fields, but also the virtues of diligence, frugality and simplicity. Next to the family, the school was the decisive factor in shaping this character.

Reading, writing and some arithmetic made up the curriculum of the little one-room school. In addition, the code of 1650 ruled that parents and schoolmasters must question children systematically each week in the principles of Christian religion. This catechism requirement persisted until 1821.

In fact, the Bible undoubtedly served as a textbook for early Stamford children, and their first learning device probably was a homemade hornbook. A hornbook was a piece of wood shaped like a paddle. Clipped to the paddle was a piece of paper protected by transparent cowhorn. The paper contained a printed alphabet, along with syllables to memorize and the Lord's Prayer, Few hornbooks were used as late as the Revolution, however, when paper had become cheaper and textbooks more plentiful.

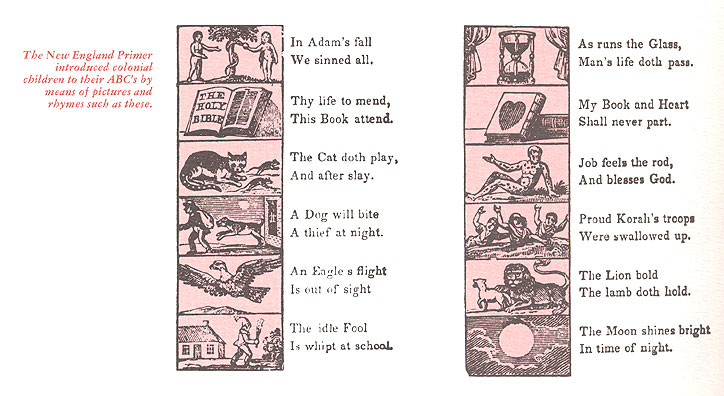

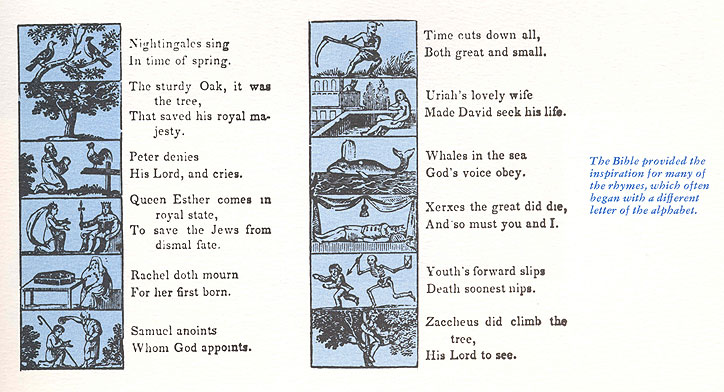

The first edition of The New England Primer appeared in 1690, It introduced children to reading by means of a series of woodcuts, each with a letter of the alphabet used in a cheerful little rhyme such as, “In Adam's fall, we sinned all,” Next came easy syllables to be recited and memorized and then words, including words like “fidelity” and “fornication.” The primer did not shrink from letting its young readers in on the sins of the biblical fathers: “Uriah's Beauteous Wife Made David Seek his Life.”

In October, 1685, the town voted to heat the school: “The town appoint ye schoolhouse to be fitted with a stone chimney and all other ways comfortably fitted for use of ye school.” In what other ways it was “comfortably fitted” are not known and somewhat difficult to imagine. At any rate, five years later the town decided it needed a larger school, and the little building was sold to Stephen Bishop for twenty shillings and sixpence.

Connecticut insisted that the towns provide schools six months of the year for children between the ages of four and fourteen – and helped to finance the schools. In 1700, the General Assembly agreed that for every thousand pounds of list value in a town, the treasurer of Connecticut would pay that town twenty shillings for educational purposes.

As Stamford grew, residents in several outlying areas asked for schools near their homes. For a while, small classes were held a few weeks at a time in such locations. Then, in 1702, two more schools were built, one on the west side of Mill River and one on the east side of the Noroton River. (Stamford territory at the time took in Darien and part of New Canaan, Pound Ridge and Bedford.)

Local authorities gave the people in the two areas the liberty to hire a “woman schoole.” (Spelling in those days was pretty much a matter of individual initiative.) Also, “ye money collected in ye county rate” was to be distributed to all three schools, according to the number of pupils in each. Although the tax had since been doubled to forty shillings per thousand pounds, pupils continued to pay “fares.” The Newfield people set up a school in 1727, and in 1734 one was established in Simsbury, north of Bull's Head, making five in all.

Originally, the town meetings handled both church and civil matters. Then in 1731, a division of administration put the Stamford schools under church jurisdiction in what were known as Ecclesiastical Society Meetings. The First Ecclesiastical Society – or School Society, as it was later called – took care of schools roughly south of the present Merritt Parkway. The Second School Society, formed some years afterward, took care of schools in the northern area. The School Society appointed “school visitors” who were delegated to inspect each school at least twice a season; without the inspections, the school would forfeit its portion of the public money. The visitors could “direct the public exercises of the youth, as well as their instructions in letters, religion, morals and manners.” Particularly, the visitors were supposed to direct the daily reading of the Bible, approve the weekly catechism instruction and recommend that the schoolmaster conclude the exercises each day with a prayer.

At that time, saving the child from the agonies of Hell was a major preoccupation in Connecticut. Although many parents sincerely loved their children, their thoughts were infused with a Puritan theology that emphasized the importance of the Hereafter at the expense of the Here. Jonathan Edwards, a fiery Congregational clergyman born in East Windsor, Connecticut, called children “young vipers.” He claimed, “Their stubbornness of mind, arising from natural pride, must, in the first place, be broken down.” In line with the spirit of the times, the piece of teaching equipment found in all Connecticut schools was the rod, and even little girls had their knuckles rapped.

Beginning in 1766, an excise tax on luxuries such as liquor and tea supplied additional school revenue. Towns that indulged more heavily received more money – from what came to be known as the “sin tax.”

From the mid-eighteenth century until the Revolution, the most popular schoolbooks in the colonies were the primer, grammar and arithmetic of an Englishman named Thomas Dilworth. The Dilworth primer appeared in Connecticut in the 1740's. Colonial printers of the time, unhampered by effective copyright laws, sometimes reprinted such English primers as their own, making whatever changes suited their fancy. One printing pirate in 1776 took a woodcut of King George III and labeled it John Hancock.

Connecticut's Noah Webster, who later wrote the first American dictionary of the English language, attacked Dilworth's teaching methods. Webster claimed that children using the Dilworth primer would mispronounce one third of the words and be burdened with so many rules of grammar that they would “abhor study.”

After the patriots defeated the British, Webster displaced Dilworth in the battle of the schoolbooks. Webster's primer, published in 1783, sold eight thousand copies in the 1790's in Connecticut alone. His primer and grammar became the standard schoolbooks for nineteenth-century Americans.

The new State of Connecticut revised the system of giving aid to local schools. Thanks to claims of land speculators before 1763, Connecticut possessed 3.3 million uncultivated acres in what is now Ohio. Five hundred thousand acres of this so-called Western Reserve were devoted to compensating Connecticut victims of British wartime raids. The remainder, nearly three mil- lion acres, was sold and, in line with a 1795 decision of the State Assembly, the interest on the proceeds went directly to the schools.

In 1801, Connecticut's Western Reserve Fund amounted to $1,242,355, a sizable nest egg at the time. This money was invested in interest-bearing U.S. Government bonds and stock of the United States Bank. The state also voted to give each school district two dollars for every thousand dollars of listed property.

By 1797, Connecticut was divided into more than 200 school societies, each with at least one elementary school. Another Connecticut native, Jedidiah Morse, who wrote the first graded series of schoolbooks published in America, concluded that the chances of getting an education in Connecticut were better than anywhere else in America or Europe. His graded geographies were widely used in the state.

On April 2, 1798, the eighty-one property owners in Stamford's First School District were invited to a meeting to discuss building a new school. John Davenport, Justice of the Peace, served as “moderator.” Those present voted a tax of four cents on the dollar on the 1797 property list in the First District to construct a schoolhouse “a little westerly from the spot where the former schoolhouse stood.” What happened to the former schoolhouse – which First District children probably attended during the Revolution – is not known. Perhaps it burned down. It was located in the vicinity of the original one-room schoolhouse.

On November 20, 1798, Abel Knap and Jonathan Husted appeared before a committee that had been appointed by the First School Society as “overseers to examine schoolmasters.” After examining their knowledge in “reading, writing and arithmetic,” the overseers recommended Knap and Husted as qualified to instruct common schools of education.“ Hezekiah Bishop and William Bishop passed a similar test the following January.

As of February, 1799, the overseers found that sixty-four pupils “generally attended” the new First District school and two schools in other districts had between thirty and forty each. Stamford children in those days went to school in winter and summer. In the spring and fall they were needed to help with the planting and in the fall, with the harvest too.

By 1802, Stamford had seven school districts: the First; West of the (Mill) River; Smith's (northwestern section bordering the Stanwich line); Roxbury; Hoyt's (northern High Ridge section); Simsbury (southern High Ridge section); and Holmes (Glenbrook-Noroton section).

In 1836, the U.S. Treasury had a surplus of nearly $37.5 million. By an Act of Congress that year, the surplus was deposited with the states in proportion to their representation in Congress. Connecticut received $764,670.60. The General Assembly, in turn, deposited the money with the towns in proportion to their 1830 census populations, stipulating that the income from the money be used for the public schools. Stamford's first “federal” aid to education, known as the Town Deposit Fund, amounted to $9,520.83.

Stamford's first graded school, the Centre School, was built at the east end of Broad Street in 1852. It had eight different grades, and it replaced the old First District School that stood in the approximate location of the original one-room schoolhouse. After a disastrous fire, the wooden Centre School was rebuilt of brick in 1867. The brick building had steam heat and eight rooms that could hold four hundred pupils. In later years it became the school system's administration building before the present Hillandale headquarters was completed in 1970.

Like school authorities today, the people overseeing the schools a hundred years ago felt that many parents should pay more attention to their children's education. Complained a School Visitors' report in 1870: “Can nothing be done to induce parents to exercise as much watch and care over the education of their children as they would exercise over a flock of poultry, half a dozen swine or a few cattle?”

Some of the schools had desks facing the walls instead of the front of the room. The boys and girls sat on long benches in front of the desks with their backs to the teacher. To see the teacher, they had to curl up their feet and whirl around.

By 1870, Stamford had fourteen schools and, in addition, shared five school districts with neigh- boring communities. The Stamford schools included the graded Centre School; the Green School (in the Meadow Street-Canal Street section since wiped out by the Connecticut Turnpike); West Stamford (Richmond Hill section); Bangall; Roxbury; Simsbury; Cove; Turn of River; Scofieldtown; North Stamford; High Ridge; Hunting Ridge; Long Ridge, and Farms (on Riverbank Road). The joint districts were Hope Street, Holmes, New Canaan, Banksville and Stanwich. School receipts that year from all: sources amounted to $15,908.55. Expenses totaled $16,330.78. Eight of the sturdy little one-room schoolhouses in the northern part of Stamford remain today, but they probably would not be recognized as such. One-room Roxbury School, masquerading as a real estate office, stands on its original wedge of hill at Roxbury and Long Ridge roads. Scofieldtown School is the dining room and kitchen of a home at 263 Brookdale Road, where it was moved from nearby Scofieldtown Road.

Farms School stayed in place at 942 Riverbank Road near Farms Road and became the living room of a home. Hunting Ridge School was sold at public auction in 1945 and moved to 42 Dannell Drive, where it serves as two bedrooms and the living room of a house. Turn of River School was moved in the 1920's a few hundred yards south to 69 Turn of River Road and made into a two-bedroom house with kitchen, bath, and combination living-dining room.

The North Stamford School was moved across Cascade Road to become the Guild House of the North Stamford Congregational Church. High Ridge School forms the center section of McLaughlin Hall next to the Ridges Methodist Church on High Ridge Road. After the pupils of the High Ridge, North Stamford, Roxbury and Turn of River one-room schools were transferred in 1914 to the new Martha Hoyt School on High Ridge Road, the city donated the little High Ridge School to the Methodist Church. Last of the one-room schools to close was Bangall, at Roxbury and Westover roads. School kept there until June, 1949. The only one of the small structures still used as a school, it holds the Sunday School rooms of the attached Friends' Meeting House.

None of the one-room schools had inside plumbing. Instead, there would be a well and in the rear, an outhouse for the boys and one for the girls. On Halloween the outhouses traditionally fell victim to spooks, and the next day the teacher would ask the strongest boys in the school – probably including a spook or two – to put the privies back in place.

Sometimes heavy winds decked the outhouses, especially at Bangall School, which stands on high ground. On May 31, 1907, the Bangall teacher, Mrs. Sarah B. Stevens, wrote to First Selectman J. E. Houghton, in part: “If you can arrange to do so, I wish you would send a man to repair the boys' outbuilding at Bangall School. The severe winds have overturned it repeatedly, and as there is a stone wall just back of it, and as it (the outbuilding) has been blown not only on that but over it, into the next field several times, it is badly racked, and the shingles have been nearly all torn off. The boys have managed to get it back every time, but it is so heavy they have been unable to fix it so that it will stay in position.

“I have asked you to send a man, if possible, because everybody around here seems to be so busy that it is next to impossible to get anything done. When I state that our flag-pole is still bare of the means for raising the flag you sent us last fall, you will appreciate the situation.”

To upgrade and equalize the quality of Stamford schools, the annual town meeting in October, 1872, took advantage of power given it by acts of the legislature and voted to consolidate the school districts under town management. The meeting elected a nine-member Town School Committee, predecessor of the present Board of Education. The new committee's first chairman, Congregational minister Richard B. Thurston, bridged the gap between the loosely-organized School Society regime and more efficient town management. Under the Society organization, for example, what was third-grade work in one school might be considered fourth – or fifth – grade in another.

One of the first things the Town School Committee did the next year, 1873, was to open the first Stamford High School in one room – Room 8 – in the brick Centre School. The high school accepted students only if they passed an entrance examination. For instance, in 1876, of the forty-seven taking the test, only twenty-eight passed.

In 1888, the high school moved into the first four rooms completed at the eight-room Franklin School being built on Franklin Street. Then, in 1896, high school students had a building all their own for the first time. That year, at the urging of Stamford's first superintendent of schools, Everett C. Willard, the original Stamford High School building, now known as Burdick Middle School, was constructed on Forest Street.

Mr. Willard abolished high school entrance examinations and, to reduce the large number of absences due to sickness, brought “physical culture” into the curriculum of the schools. Physical culture led to school doctors, nurses, dental technicians and organized athletic programs.

Private schools also flourished in nineteenth-century Stamford. Perhaps the best known were two boys' schools: Betts Academy, founded in 1838, and King School, 1876, and two girls' schools: Catherine Aiken, 1855, and Low-Heywood, 1865. Today, King and Low-Heywood (now Low-Heywood Thomas) flourish on adjacent sites on Newfield Avenue.

The Catherine Aiken School closed in the 1890's, and Betts Academy, after burning to the ground, closed in 1908. Before Georges Clemenceau became World War I premier of France, he taught French at Catherine Aiken and eloped with one of his students, Mary Plummer. Playwright Eugene O'Neill in his youth was a rebellious student at Betts Academy.

In 1914, the School Committee decided to name schools after persons, not streets or locations. Individuals chosen for this honor fell into three categories: School Committee members, superintendents or principals.

Doctors and dentists in those days found time to serve on the School Committee. As a result, four schools bear the names of physicians: Cloonan Middle School, John J. Cloonan; Rogers School, Francis J. Rogers; Ryle School, John Ryle; the old Rice School, Watson Rice. One, Dolan Middle School, is named after a dentist, Walter Dolan.

Willard School honors the first superintendent, Everett C. Willard, and Burdick Middle School, the first assistant superintendent, Oscar L. Burdick. Schools named after principals include Murphy, Miss Katherine T. Murphy; Stark, Miss Julia A. Stark, and the old Hoyt School (now used by the school system for coordinators' offices and staff development programs), Miss Martha Hoyt. In recent years the policy has reverted to naming schools after locations rather than persons.

The present Stamford High School was completed on Strawberry Hill Avenue in 1928. As the city continued to grow, Rippowam High School opened on High Ridge Road in 1961 and Westhill High School on Roxbury Road in 1971. Since Rippowam opened, the proportion of black and other minority students has been balanced in each high school. Through redistricting and busing, a balance of minorities has been achieved in each of the four middle schools (seventh and eighth grades) since 1966, and in most of the seventeen elementary schools since 1972. Of the 19,118 students currently enrolled in the school system, 24.6 percent are black, 6 percent are Spanish-speaking and .8 are Asian.

Public school enrollment hit a peak of 20,960 in 1969. Since then enrollment has dropped off, due mainly to a decline in the birth rate, which shows up in the elementary grades. A lesser factor is a slowing of in-migration to the city.

J. M. Wright Technical School in Scalzi Park was known as the State Trade School when it opened in 1919 on Schuyler Avenue. The Stamford Branch of the University of Connecticut on Scofieldtown Road, which began in 1951 with a two-year curriculum, will eventually become a four-year college.

Stamford public schools no longer have a religious orientation, but a number of highly-regarded schools do. All twelve Catholic schools, including Stamford Catholic High School on Newfield Avenue, are of twentieth-century vintage. So is the Bi-Cultural Day School (secular and Hebraic studies) on Colonial Road. It opened in 1956.

Most Stamford children start school today with more general knowledge in many respects than the Mr. Bellamys and Mr. Riders of the seventeenth-century one-room schoolhouses ever in their lives possessed. Education helped set America free – and keep America free.

© Stamford Historical Society

original © 1976 by Stamford Bicentennial Corp.

Photo Selection of the Month: One-room School Houses

William Street School, 1892

back to top