The Stamford Historical Society Presents

Pride and Patriotism: Stamford’s Role in World War II

Online Edition

The Interviews

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The book may be viewed at the Marcus Reseach Library of the Stamford Historical Society.

With permission by the author.

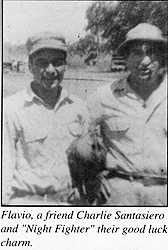

Flavio Fogio

Flavio was drafted in 1941 and served the 192nd Field Artillery Battalion. This unit included scores of Stamford boys because it was originally a branch of the National Guard which was called into service when the U.S. entered the war. The 192nd was attached to the 43rd Division Artillery which saw action in the Pacific including Guadalcanal and the Philippines.

Our job was to act as support for the infantry. We operated 155 mm howitzers which shot a 961b. projectile. It had a range of about 7 miles and would sometimes leave a crater 35 feet in diameter. Under the right conditions, we were extremely accurate …maybe within 20 yards. The Navy would bring us in and we would set up right on the beach.

I first saw action in February 1943 at Guadalcanal. Our job was mostly mopping up, but that’s where we got our first taste of aerial bombing. One night when we were on the beach, the Japanese bombed us. Guys were digging holes in the beach with their helmets and their hands. That’s how scared we were. Antiaircraft, search lights, guns going off all around us – you’ve never seen such a spectacle.

Our job was to act as support for the infantry. We operated 155 mm howitzers which shot a 961b. projectile. It had a range of about 7 miles and would sometimes leave a crater 35 feet in diameter. Under the right conditions, we were extremely accurate …maybe within 20 yards. The Navy would bring us in and we would set up right on the beach.

I first saw action in February 1943 at Guadalcanal. Our job was mostly mopping up, but that’s where we got our first taste of aerial bombing. One night when we were on the beach, the Japanese bombed us. Guys were digging holes in the beach with their helmets and their hands. That’s how scared we were. Antiaircraft, search lights, guns going off all around us – you’ve never seen such a spectacle.

Once we were on this island, Koka Rona, in July 1943. It wasn’t occupied by the Japanese. We were only supposed to protect the Sea Bees while they built an airfield. All of a sudden, a squadron of Japanese bombers came in. I don’t know how many there were, but what a sight! We were not prepared for them. We didn’t even have our antiaircraft in place yet. They must have killed about 100 Sea Bees …it was terrible. Over the next few days, we got our equipment in place. Then, on July 4th, I’ll never forget it, this big squadron of Japanese planes came back for the kill. They were flying low. They probably thought they’d hurt us again. But this time our antiaircraft batteries just threw everything at them. There were 28 or 30 bombers, and we shot down every one of them. Not one of them got back home to tell what had happened.

They were in such close formation that one would explode and take another down with it. We talked about that July 4th for quite some time. We also saw a lot of fighting at Munda, in the Solomons. (This is an understatement. The War Department later said that at Munda, the 43rd “assured its place as one of the great fighting divisions of the U.S.”)

Sometimes the enemy was malaria. We were given a drug to take, but the rumor went around that it made you sterile so a lot of guys wouldn’t take it.

Usually we set up on the beach well after the infantry went in, but at the Lingayen Gulf in the Philippines, we landed only a half hour after H-hour. We ended up pinned down on that beach for 9 days. I didn’t take my boots off for 9 days.

There is no doubt that our toughest fighting came during our a ssault in the Philippines. Every night, we had to fight like the infantry because the Japanese would try to infiltrate. One night, the Japanese rolled grenades down at us from a hill. The order at night was to shoot anything that moved. One night one of our own guys was killed. He went to get something from one of our trucks that was outside the perimeter. The next thing you know, he was shot.

ssault in the Philippines. Every night, we had to fight like the infantry because the Japanese would try to infiltrate. One night, the Japanese rolled grenades down at us from a hill. The order at night was to shoot anything that moved. One night one of our own guys was killed. He went to get something from one of our trucks that was outside the perimeter. The next thing you know, he was shot.

The following night we set up our perimeter, and I was laying down near a stone wall close to the perimeter. I shouldn’t have been there, but it was a quiet night. All of a sudden, I hear a noise, and I got up and saw a figure walking down a dirt path. I drew a bead on this guy. I should have shot him, but the only thing I could think about was what happened to our guy the night before. I couldn’t quite make out the figure, but he was walking so nonchalantly. A few seconds later, there was a burst of fire. Sure enough, it was a Japanese soldier with five grenades. He was probably trying to sabotage one of the howitzers.

After a while you wouldn’t believe how proficient the gun crews got with the artillery. It was supposed to be an eight man job, but sometimes we had to do it with five – especially when you were going 24 hours at a time. One time, the antiaircraft shot down a Japanese plane made by Mitsubishi. When we looked at the wreck, we saw that the ball bearings were made by Norma Hoffman in Stamford.

I had enough points to be discharged, so in August of 1945, I was on my way home. I was on the high seas when the war ended. I heard that we dropped the Atomic Bomb, and my first reaction is, “What the hell is the Atomic Bomb?”

We did lose two Stamford guys in our division, George Fielding III and John Mownn. John was a forward observer. He used to go out into the jungle for three days at a time. John’s three days were up, but he stayed three more. While he was out there he was killed by a mortar. When I got home, I went to see his father. They had a big farm on High Ridge Road. His father was wearing John’s watch. He said to me, “Whether this watch works or not, I’ll wear it till I’m dead.” I felt so sorry; I wished I had never gone to see him.

When I came home, we didn’t have psychiatrists or anything. The thing that surprised me was that nobody asked us anything. The people back home must have been told, “Let them forget about it.” Nobody asked you anything. It was like you never left home.

I will say one thing, though, everybody has high points and low points in their life. I’ve had a good life, but thinking back on it – if it wasn’t for my war experience, I just don’t think my life would have been as important.

Flavio left the war as a First Sergeant. In March of 1945, he was awarded the Bronze Star for "remaining cool under hazardous conditions and inspiring men under him” during the invasion of the Philippines.

192nd Field Infantry*

During the Second World War hundreds of Stamford boys fought with the 192nd Field Artillery Battalion. The unit, originally founded in Stamford in the late 1600s, was involved in every military engagement from colonial times right on through World War II.

The 192nd served with distinction in the Pacific most notably in the Philippines and Solomon Islands. The unit also played a critical role in rescuing a young Navy officer, John F. Kennedy, after his PT Boat was split in two by a Japanese destroyer. When Kennedy carved his help message into a coconut shell, he gave it to a native who in turn brought it to Everett Robinson, a resident of Greenwich, and member of the 192nd. The rest, is still history.

The unit was headquartered in Stamford until 1971 when it moved to Norwalk. Due to military downsizing, and the newer self-propelled artillery units, the need for the 192nd was greatly diminished.

Finally, in 1933**, after over 300 years of service to this nation, the 192nd was deactivated. It remains however, the nation's oldest field artillery unit in continuous service and one of the oldest regiments in the U.S. Army.

© Anthony Pavia, 1995

* Editor's Note: This should read 192nd Field Artillery.

** This is a typo. The 192nd Field Artillery was deactivated in August 1993.

The Battle of Guadalcanal

The Battle of Luzon

Battle of New Georgia (Munda Point) Wikipedia with the usual caveat

2nd Battalion - 192nd Field Artillery Regiment

Lineage and Honors 192nd Field Artillery Battalion

Lineage and Honors 192nd Field Artillery Battalion

Introduction

Veterans

Battles

Stamford Service Rolls

Homefront

Exhibit Photos

Opening Day