The Stamford Historical Society Presents

Pride and Patriotism: Stamford’s Role in World War II

Online Edition

Four Stamford Buddies

Left to right. Paratroopers Ben Vincent, John and Stanley Kaslikowski, John Buchetto, all of Stamford, all in the same [outfit] "seeing plenty of action" on the Anzio beachhead. After writing his parents about a bomb the "landed close enough to spit on." Vincent said the most important thing that happened was that the four buddies were together. (Clipping and photo courtesy Dan Burke Jr.)

The Interviews

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The book may be viewed at the Marcus Reseach Library of the Stamford Historical Society.

With permission by the author.

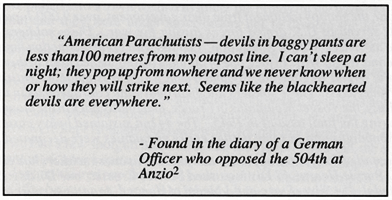

Stanley Kaslikowski

The Kaslikowski family sent four of its boys off to war. Coincidentally, two of them, Stanley and his younger brother John, became paratroopers in the 82nd Airborne. Both boys also ended up in the 504th Parachute Infantry nicknamed the “Devils in Baggy Pants.” Stanley had 3 combat jumps and took part in the invasions of Salerno, Anzio, and Holland as well as the Battle of the Bulge. His first jump, however, was during the invasion of Sicily in 1943.

In training I never saw John, but when I was at Fort Bragg I was doing a parachute jump and got stuck in a tree. Someone landed near me and when he heard all the thrashing, came over to help. It was my brother. He just started laughing when he saw it was me. We went overseas together and ended up in the same battles.

In training I never saw John, but when I was at Fort Bragg I was doing a parachute jump and got stuck in a tree. Someone landed near me and when he heard all the thrashing, came over to help. It was my brother. He just started laughing when he saw it was me. We went overseas together and ended up in the same battles.

My brother and I were not supposed to be together as paratroopers. The army did not like two brothers in the same outfit. We did our training in French Morocco. We had sand models of the drop zone that we’d been studying. It was so hot there that most of our training was done at night – except the jumps. They considered it too risky to practice those at night. But our commander Lt. Mills pulled some strings so we both ended up together.

I’ll never forget Sicily. It was July 11, 1943, my birthday. 1 was 27 years old that night. We left from French Morocco and were in the plane 3 or 4 hours. When we got near Sicily the antiaircraft opened up. I think it knocked down over 20 of our planes. (In this tragic incident at Gela, 27 American planes were shot down, most of them by U.S. Navy ships.)

The pilots wanted to drop us as soon as possible. We were supposed to be dropped near a beach but were nowhere near it.

When I jumped I couldn’t see that well. I couldn’t see the ground so I came down hard on a railroad track. I didn’t feel it though because your system is like a boxer’s. Your adrenaline is pumping. You are tense. Then I heard some rustling but I didn’t know who it was. We all had a certain code word to use when we landed so I yelled out, “Apple”. Luckily it was another guy from my outfit. Pretty soon about ten of us got together, including Lt. Mills. We started walking down a road. We kept hearing this noise. I could swear it was an enemy tank but I didn’t say anything. So we kept on going until we got to this bridge that went over a small valley. We hit the bridge and were almost at the end when we met the Germans. I think that Lt. Mills fired first. I didn’t even have a chance to get my rifle. There was a quick fight. I dove off the side of the bridge and that’s when I got captured. The Germans got us into a group and a soldier had his rifle pointed right at my head. I thought he was going to shoot. Finally I just made a run for it. Another shell came in and that’s when I got hit. The guy next to me got his arm blown off. Lt. Mills also got hit pretty badly. All the while the Germans were yelling in English “Halt.” I was hit in the arm and the leg but managed to get away. That night, in all the confusion, I dug a foxhole to protect myself. I had to do it with one arm. I was very lucky it was only for one night. The next morning the Americans came in and rescued us.

I was taken to a First Aid Station and who did I run into? Leon Dzilinski. We were neighbors down in the South End. We only lived a block from each other. He told me our plane was lucky because it was our men that were firing at us. About a half hour earlier there was a German raid and the Navy antiaircraft thought that we were the Germans coming back. I was also lucky when I was captured because it was a U.S. Navy shell that came in and allowed me to escape. I still have a souvenir inside my leg to prove it. After the First Aid Station I was taken to Africa and was in the hospital for six weeks.

The next jump we made was at Salerno. They had us jump there to help out some of our troops that were being pushed back to the water by the Germans. The jump itself was not so bad. It was during the day and we didn’t have too much action. But later, when we fought in the mountains near Cassino we had it rough. It was very cold and we had to carry so much equipment. I was in charge of the 30mm machine gun. It only weighed 30 pounds but you had to carry that with all of your other stuff. And we were climbing up mountains the whole time. In combat you never walked around something. You had to go through it. We walked through everything – creeks, lakes, everything. You’d be wet up to your waist and it was miserable. We had to be careful about mines too. And after all this, you’d dig a foxhole and have to sleep in it at night. You were lucky to get 2 or 3 hours sleep.

We did all of this climbing while we were fighting the Germans. One night we overran an enemy position and during the fight I jumped into a foxhole and there were two dead Germans in it. I had to stay there all night with them. We were under fire and it was cold. You had to get used to things like that. We fought in Sicily for about six months and then in January 1944, we hit Anzio.

At Anzio I got hit again. We were fighting at a place called Mussolini’s Canal. We were on one side and the Germans were on the other. They had some houses and buildings on their side and were protected. We weren’t. We were out in an open field. German planes were coming over and hitting us and all we could do was stay in our holes. Our own planes were not able to support us because of the weather.

At Anzio I got hit again. We were fighting at a place called Mussolini’s Canal. We were on one side and the Germans were on the other. They had some houses and buildings on their side and were protected. We weren’t. We were out in an open field. German planes were coming over and hitting us and all we could do was stay in our holes. Our own planes were not able to support us because of the weather.

The Germans had these mortars set up behind the houses and they were firing on us. One of the shells came in and made a direct hit on a foxhole right next to me. It blew the guy’s body to bits. The shells just kept coming and finally a few of us decided to make a getaway . That’s when I was hit in the leg. I was lucky again because the poor fella next to me lost his leg. I just ended up with shrapnel.

They took me to the hospital and four days later they brought my brother Jack in. So here I was in one bed and my brother in the one next to me. Jack was hit in the foot but was lucky too. It wasn’t bad. (This incident was reported in the Stamford Advocate but incorrectly had Jack as the first brother wounded.)

You know, in a way, sometimes you were better off once you got hit. You got to rest up. It was like heaven. You were in a bed, you had clean white sheets. Nurses taking care of you. When you were out fighting you were in these mud holes, cold all the time and you couldn’t even leave the foxhole to go to the bathroom.

(In September of 1944 the 504th was called upon to make a jump into Holland. Their mission was to occupy bridges which spanned the large rivers of central and southern Holland.)

After I recovered I made the jump in Holland. We were supposed to be reinforcements for some British and Polish paratroopers who were dropped miles from their zone. They were slaughtered. We were supposed to take a bridge. The Germans controlled one side of the bridge so we had to cross the river and fight them on the other side. Rubber boats were dropped in and we crossed. We were loaded with equipment and if anything happened to our boat we wouldn’t be able to swim. We were under fire but our boat made it across without too much trouble. By the time we got across it was getting dark and we fought most of the night. (This incident took place at a bridge across the Waal River in Nijmegen. Of the 26 boats that made the initial trip across the river, only eleven were able to transport succeeding waves of paratroopers.)

On the other side of the river we were dug in. A few of us were in a foxhole all night. About ten feet away we heard movement all night and I figured it had to be one of us. When light came the next morning we went over and there was a young fella, maybe 18 or 19 years old. He was Polish but fighting for the Germans. I spoke Polish so I talked to him. I asked him why he was fighting for the Germans. He said, “Look, I’m a prisoner. I was forced to do this.” He could have easily thrown a grenade into our hole during the night but thank God he didn’t. We finally pushed the Germans back and took the bridge.

My last battle was during the Bulge. We had been fighting for months and were due for a rest. Instead while we were in France, the Germans made their breakthrough. So late on a Sunday night we were told that we had to go back to the front. We were hauled out and made about an eight hour drive to Belgium, outside a town called Cheneux. The Germans held part of the town and we had to cross a wide open field with barbed wire. We had to crawl like snails. It was cold and there was snow on the ground. Some of the guys would straighten up to climb over the barbed wire and were shot immediately. I was able to crawl over to a small group of trees. It was at night and we could hear the enemy but couldn’t see them. They had these big flak wagons and were opening fire on us. We fired back but with one machine gun we really couldn’t do that much damage. Then, a round came in, hit a tree and part of the shell got me right in the chest. It felt like I got hit with a sledgehammer. I fell down to my hands and knees and that was it for me.

(The combat record of the 504th indicates that the men had to cross a 400 yard field that had barbed wire placed at 15 yard intervals. Little cover was available and enemy fire was the heaviest ever faced by this unit. Despite these conditions the Americans succeeded in taking Cheneux by the following day.)

I was in the hospital for over a month and I couldn’t use my left arm for a while. Because I was wounded so many times they decided to send me home. I came home in a hospital ship. That’s when it finally got to me. My nerves were shot.

I don’t regret joining the service even with all of my injuries. But I have to tell you that I could never do that again. But, when you’re in your twenties, you’re crazy. You’ll do anything.

Today I consider myself a lucky man that I didn’t lose an arm or a leg. When I go to the V.A. Hospital and I see guys without a limb, some walking around like zombies, I’m just happy I’m able to talk about it all with you today.

Stan was awarded three Purple Hearts for his wounds. He received four Battle Stars, the Combat Infantry Badge, and a Presidential Unit Citation. He returned to Stamford where he operated the Waterside Food 0 Mat for over twenty five years. He still carries shrapnel in his left leg as a permanent reminder of the war.

© Anthony Pavia, 1995

Introduction

Introduction

Veterans

Battles

Stamford Service Rolls

Homefront

Exhibit Photos

Opening Day