The Stamford Historical Society Presents

Pride and Patriotism: Stamford’s Role in World War II

Online Edition

The Interviews

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The book may be viewed at the Marcus Reseach Library of the Stamford Historical Society.

With permission by the author.

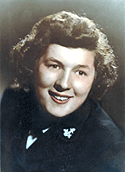

Ruth Maurer Miller

Ruth Maurer graduated from Stamford High School in 1939 and went to work as an artist for Condé Nast. After Pearl Harbor, she joined the WAVES and served with the Hospital Corps in Oklahoma, Tennessee, and New Orleans.

I did my basic training at Hunter College in the Bronx, and then we were sent down to Corps school in Hadnot Point which was attached to Camp LeJeune. In fact, we went through a little commando training while we were down there. I guess they figured that if push came to shove and something happened, we would be able to take care of ourselves because at that time they weren’t sending the WAVES overseas.

I did my basic training at Hunter College in the Bronx, and then we were sent down to Corps school in Hadnot Point which was attached to Camp LeJeune. In fact, we went through a little commando training while we were down there. I guess they figured that if push came to shove and something happened, we would be able to take care of ourselves because at that time they weren’t sending the WAVES overseas.

During Corps school training period, I did special duty for a female Marine Sergeant who had a breakdown. I sat in the room with her, with the door locked, like a private nurse. She’d lie there and stare at the ceiling for hours, but at times she was violent. One night while I was on duty, she got up to go to the bathroom. When she came out, I had my back turned and I don’t know what made me turn around, but when I did she was standing there with a chair ready to clobber me. I did a swan dive and tackled her and screamed bloody murder. There was supposed to be a corpsman on duty in the hall, but for some reason he wasn’t there. Finally, the head nurse came in and we subdued her.

From there I went out to Norman, Oklahoma. When we got there, no one warned us about the water. It was filled with Epsom salts; you could taste it. Well, those latrines got quite a work out the first few weeks we were there. After that we drank Coke. The Coke machine was always empty because as soon as the guy came to refill it, we’d line up and start buying it. To keep it cool, we used to store it between the windows and the screens of our barracks. One night a few of the bottles froze and started popping and we thought people were shooting at us.

Norman, Oklahoma was a hospital discharge center. For a while I was assigned to the quarantine ward where there was an outbreak of spinal meningitis and scarlet fever. Then, I was assigned to Ward 8. That was for fellows who came back from the war mentally shattered. It was horrible… padded cells, the works. The only thing I’ll talk about was this one case where a Marine had combat fatigue and he thought he was Jesus. His father came to visit him and I was absolutely horrified when his father reamed this boy out. He was probably only 17 or 18 years old and the father called him a coward and told him that he was not a patriot and on and on. I finally had to call a doctor. When the doctor got there he told the father to get out and never, ever come back. I don’t know what happened to this kid, or any of the others. I don’t know if they recovered or not. But I won’t talk about the other things I saw there. It was just such a shame that such young boys came back with no minds.

In Norman, all you saw were these big oil rigs all over the place. Even the state capital building had one on the lawn. Out there the cities were dry. No alcohol was allowed. It was tough for sailors to sneak alcohol back to the base because they were searched as they came back. But the guards never bothered us so we used to bring it back for the sailors. We’d go into town and make friends with the bellhops because they’d always be able to get “white lightning” for you. We used to wear our long overcoats and fill up the inside pockets with pints or half-pints. The shore patrol never searched us, but one of them used to joke with us and say, “I’ve never seen so many thin women come back to the base so fat.”

After Oklahoma, I was sent to New Orleans. Because our barracks weren’t finished yet, we stayed right in dorms at the Air Station down there. It was a fascinating city with lots of history. I was stationed at the Naval Hospital there. We had a couple of pilots who were burned very badly and I hope I never have to see anything like it again.

Segregation was also very bad down there. If you got on a bus and there were no more seats, one of the Blacks would have to get up and give you their seat. Here I was, about 20 years old and I thought I knew everything. Boy, did this really open my eyes. Once I wanted to have the handle on my suitcase fixed, so I brought it to a man who used to fix the ambulances on the base. He could fix anything. When he gave it back, I thanked him and offered him some money, but his boss, a white guy said, “You don’t have to give that Negra anything.” I was shocked and said, “Well that’s the way I was brought up.” I offered the money again but he wouldn’t take it.

I finally ended up in Memphis, Tennessee, at the Millington Air Station where I did dispensary (infirmary) duties. Again, there, Blacks were segregated even in the dispensaries. I was there when the war ended.

Overall, it was a very rewarding experience and I’d recommend it to any young woman. It was enlightening and I did some things I never thought I could do. But there was a war on and you rose to the occasion. You did what had to be done.

Ruth returned to Stamford in 1945, married and raised 3 boys. Along with her husband, she operated “Bob’s Diner” which was a fixture in Glenbrook for over thirty years.

© Anthony Pavia, 1995

Introduction

Introduction

Veterans

Battles

Stamford Service Rolls

Homefront

Exhibit Photos

Opening Day