| Join | Official Historian | City of Stamford | Blog | About Us | |

| Jewish Historical Society | Civil War Roundtable | Contact Us | |

|

|

|

|

Photo Archivist's Selection of the Month: July 2007The Nature Studies and Recreations of a Business Man

Volume III, Number 3, July 1910

|

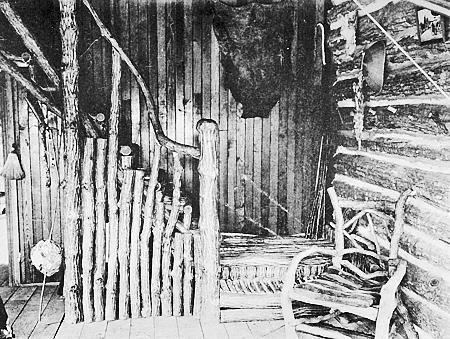

THE RUSTIC STAIRWAY IN THE CABIN. |

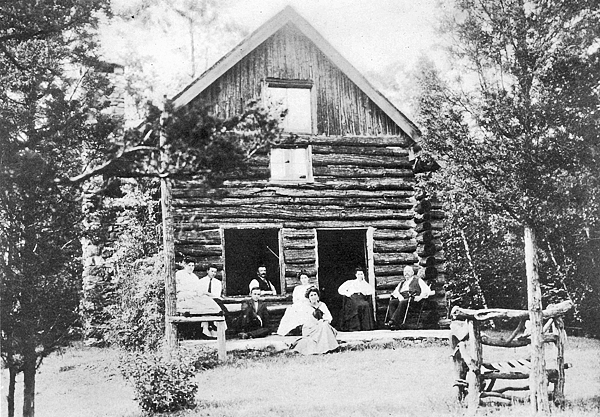

About twelve years ago, shortly before disposing of his long established business, Mr. Hoyt built a log cabin in the primitive woods at the north of Stamford and, as thousands of others have elsewhere done, went for several years as to a place of rest for himself, his family and his friends. But if this were all, there would be no excuse for the presence of this article in THE GUIDE TO NATURE.

A few years ago the woods revealed themselves to him. Thoreau said he always felt alarmed if he walked a mile in the forests without entering them. If he had known it it, like thousands of others who have carried a bit of city into the country and have thought they were really within touching distance of nature, Mr. Hoyt had more cause for alarm than Thoreau, because he had not as yet come to understand and appreciate the inner life and the inspiration that come from nature, and for which a few of us plead, and for which we are so unkindly misunderstood by thousands who wag the head at us and pass by on the other side.

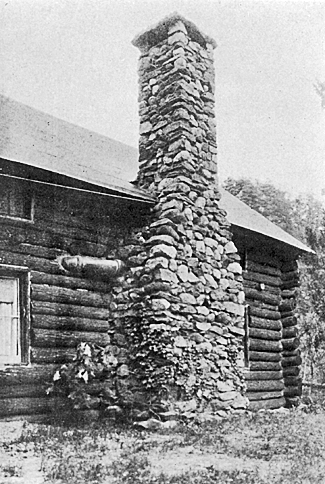

THE SUBSTANTIAL AND ATTRACTIVE CHIMNEY OF THE CABIN. |

More than ten years ago I photographed his cabin, merely as an act of friendly courtesy, and never made mention of it in any form because he, like so many others, had not gone to nature only because he had built a cabin in the woods.

But within the past few years, nature "understanding and intimacy" have come and are coming in joyous, inspiring, enthusiastic measure.

The reader is aware that the writer has known many great naturalists, and for that reason my remark should have some weight when I say that not one of them had a more genuine love for nature than has Mr. Hoyt. He will object to my saying this, and I do not say it to exploit him, but to hold out hope to you. O business man, in activity or retirement, that may get to nature—YOURSELF, not merely your bungalow, your cabin, your money or your acres.

How do you get there, Mr. Hoyt? I inquired.

"Break away; but if you do that, you've got to try and try hard. There is so much to see, so much that is good, that life isn't long enough to look around and see it all. There are no two days alike. The woods and fields and flowers are different every day. There is more inspiration there than the man who seeks only wealth can ever find. Get a big lot of wealth, get many things to care for, and then there is trouble. I do not want to go to the big gatherings. I go away from them to the woods. Only one thing I regret—it seems so selfish; I get so much of nature's wealth, and so many other people get so little. I try to tell them, but they are deaf, and I give it up. It takes a long time to know much of nature. It is difficult to tell people how to do it. Do you know how, with all your experience? No, don't answer; I know you don't. Nobody told me how, and if he had, I could not have done it on his plan. I sought it alone and nature revealed herself to me. It is painful to see the indifference of others. But I shall continue to observe whether they do or do not. Only now and then one, but if you get only one, you are doing great good. It is delightful. You cannot explain it. You've got to feel it, as the Methodists say."

And then I interrupted; the worst of it is you are sometimes, perhaps many times, perhaps many times, misunderstood by the professional naturalist. Did you understand this when you were in business?

"No it all came to me later, when I forgot the store and let myself loose in the wood."

Now do not mention this, will you, Mr. Hoyt? Some of our "best" naturalists and scientists are still in the store—classifying, arranging, collecting, dusting, packing canning, talking, haggling over detail, selling, walking around and around their own counters, keeping their own books and—

Mr. Hoyt interrupted. He slapped me on the knee.

"Sat, are you talking to me about my store—Oh, I understand! Yes, perhaps there are others. I did not get to nature through the 'store' interests. And perhaps some of your customers do not understand you when you are in the store and they ar in the woods. But it isn't only the city man who misunderstands? The city man can get to nature as easily as the country man."

How often do you get out to the woods?

"Every day. All weathers are good; it is just the same in winter as in summer; always good and beautiful. What you do not see at one time, you will at another. Nothing more beautiful than icicles, snow and frost. All outdoors is a continuous panorama at all times."

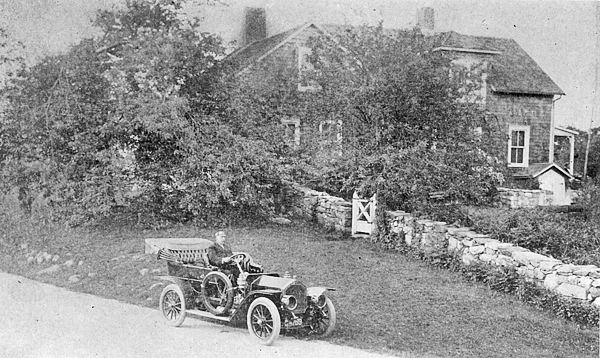

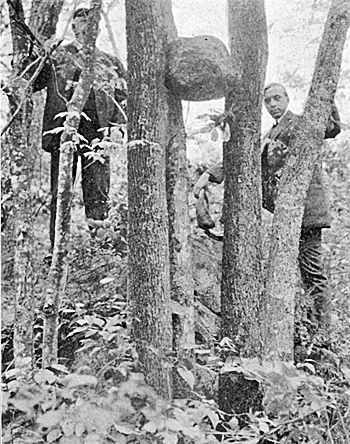

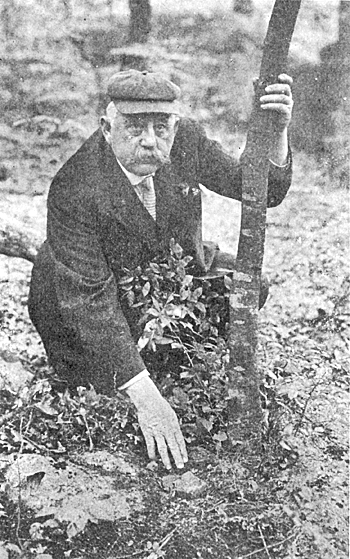

MR. HOYT STARTING ON AN EXCURSION FOR MICROSCOPIC LIFE IN THE MARSHES.

Do you keep a record of your observations and make collections;

"Not a bit. I couldn't take time to read the records or examine the collections. Every day has enough new things.The book is too large and too interesting. We must keep on reading ahead. Life is too short to go back and re-read. I can sit down in any place and at any time and right there and then see and hear enough that is new. What's the use of yesterday?"

RESTING ON THE ROCK COUCH IN THE WOODS.

"See! It fits so well it feels soft."

You find it also physically beneficial?

"Yes, I practice deep breathing in the woods. Stand up this way," as he then illustrated, "throw the shoulders back and breathe in—so. Why the woods are full of oxygen. Seems to me more there than elsewhere. And why not? The scientists tell us the leaves are giving out oxygen. It seems to me to be in the air strong and inspiring. No place equal to the woods for good breathing. I have no rule. I go as I see fit. I believe I can thus 'stave off' a cold."

Mr. Hoyt advocates crushing the various aromatic leaves and enjoying their odor. Thoreau also advocated this, and the Japanese ideally practice it by organizing parties which visit the woods for this purpose. Mr. Hoyt puts it as follows:

"There is an aroma exhaled by certain trees by which they may be recognized at a considerable distance. Did you ever smell the cedars on a hot day? The have a curative quality."

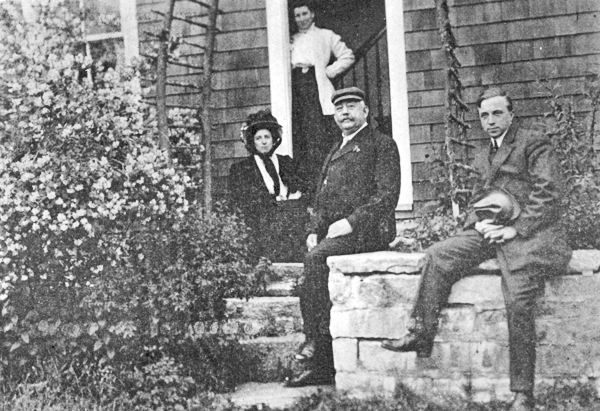

MR. HOYT AND THE WRITER UNDER THE GIANT OAK.

Mr. Hoyt also believes that "Some of the most beneficial things are so simple that most people won't practice them. I believe in outdoor bathing in a brook or pond. It is a good thing even to take an 'atmosphere bath' in breezes or sunshine."

THIS BOULDER HAS BEEN "UP A TREE" FOR SEVERAL YEARS.

|

As he saw me taking notes, he said: "I don't want that. I do not want you to tell about this. I'm just talking to you personally as a naturalist, telling how I do it . . . I know people who cannot sleep at night. Better be up in the woods and let nature cure them . . . May loose their money. This is the true wealth. No one can take it from you. In boyhood I didn't know it. Never knew it till I got out of business and then I went to Old Mother Nature and get what I couldn't get elsewhere and what money couldn't buy.

"JUST LOOK AT THAT:

ONLY A LITTLE CRACK, AND IT SEEMS AS IF THE

THREE IS GROWING OUT OF THE ROCK."

"I went to Jerusalem, Old Spain, the whole length of Italy, Germany, France, England, Asia Minor, Egypt and the Pyramids; but in none of these did I find the equal of what I find in the woods. Nature does not advertise. You go by her, you spit on her, abuse her, but there she is with arms wide open, trying to help you and everybody else. I was fifteen years 'at it' before I knew it was there. It's a nice thing to get something of value that isn't mixed up with dollars. One gets tired of the rush everywhere for dollars. Go and sit in the woods and get out of it. You cannot get it under the electric lights where everything has a label on it. But do not go at it with a business method.

I do not care whether I catch the bug or not; if it escapes, I surely have had the benefit of seeing it. But it is like fishing—one cannot always get the fish. Sometimes, you know as they say, 'The won't bite.' But there are times when you can get 'a whole mess.' But do not misunderstand. You cannot say to all the pretty things, 'Come,' and have them come. They do not obey in that way. I know I am getting satisfaction, but I can not tell it to others—not as I understand it. But I know it is all right. I wish the whole world could get some of it. I wouldn't hurt them but would do good. I just 'grab' what I see, if it comes to me in its own sweet way."

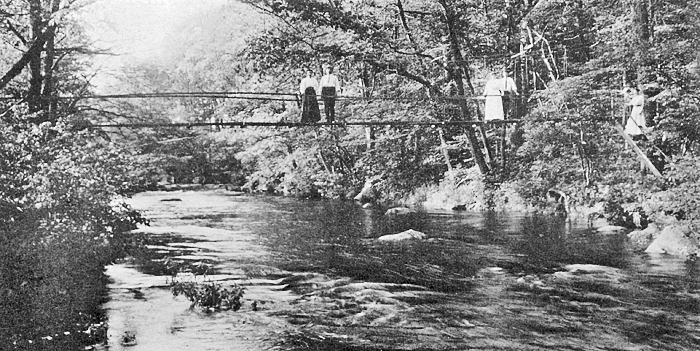

A GAME OF QUOITS.

In which Mr. Hoyt is very skilled.

And then he told of watching a song sparrow teach her young, of a humming bird alighting on a wire of the cabin so that he could closely observe it, and then added this philosophical statement:

"Don't worry of you forget some of the observations. Plenty new each day to keep one busy. There is something in solitude which many people do not understand. Go alone—but you will not get a diploma; you never graduate, nature gives final degrees, but there is no end to the honors that she can confer.

"A man who studies nature reads folks better. You learn to appreciate all kinds of people. It takes many different things to make up nature. You recognize that each has its place. So it is with all kinds of people."

To induce you to have an "understanding and intimacy" in your own way with nature, to get value equal to that of Mr. Hoyt's is the purpose of this article and of this magazine, and the object of the writer's life.

Another cottage in North Stamford: A Woodland Home Made of Packing Boxes

Other Photo Archivist Selections of the Month

Photo Collection Information

Another article from

Another article from  ANY years ago, I read a statement made by some prominent naturalist to the effect that the best naturalists do not write, lecture, teach, collect, buy nor sell.

ANY years ago, I read a statement made by some prominent naturalist to the effect that the best naturalists do not write, lecture, teach, collect, buy nor sell.